In Memoriam:

Tom Hayden

1939-2016

A Tribute to Tom Hayden

by Judy Gumbo at Tom’s Memorial

Mechanics Institute, San Francisco, 2.9.17

It’s a privilege and very emotional for me to remember Tom Hayden, another of my pals who has gone to that great Movement demonstration in the sky. The Tom I knew is mostly hidden today: a passionate and dedicated human being who was also a political extremist. To my knowledge, Tom has not written much about the specifics of his ultra-radical days – 1968, 1969 and 1970 – but in my opinion that same passion for fundamental change that propelled Tom when I knew him best remained with him throughout his life, although it presented itself in different guises. You will certainly find that passion in his posthumous book Hell No.

I first met Tom in Chicago’s Lincoln and Grant parks at the police riot during the 1968 Democratic convention. I ran beside Tom from the tear gas and was there when he was pushed through a plate glass window in front of the Hilton Hotel. After Chicago, Tom, my late husband and Yippie founder Stew Albert, and I roomed together in Oakland in a house owned by Ramparts editor and anti-war Vietnam vet Don Duncan; Tom, Stew and I then moved to 2917 Ashby Avenue, from which Tom quickly moved on to live on Bateman Street with his then girlfriend Anne Weils. I was not surprised to find out recently from Becky O’Malley, editor of the Berkeley Daily Planet, who lives across the street from the Ashby house, that her next-door neighbors had confessed to her they allowed FBI Agents in to surveil us.

1969 was People’s Park Spring. Berkeley was under martial law, public meetings of more than three people were forbidden. Tom called together a group of 20 of his closest friends. Including Steve, Stew & me. Tom beckoned; we responded. We met at an art-deco hotel in Oakland and put together what we titled The Berkeley Liberation Program. Modeled on the Black Panther Party 10 point platform and program, Tom’s goal was to set out a political vision for Berkeley and the world. This vision, like the Port Huron Statement, would be democratic, participatory and ultimately socialist. “The People of Berkeley,” it began, “passionately desire human solidarity, cultural freedom and peace.” It ended with a rallying cry that with a few, very notable exceptions, I feel is as appropriate today as it was in 1969.

Unite for Survival

Resist and Create

Fight for a Revolutionary Berkeley

With your friends, your dope, your guns

Form Liberation Committees

Carry out the Program

Choose the Action and Do It

Set Examples & Spread the Word

POWER TO THE IMAGINATION

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE

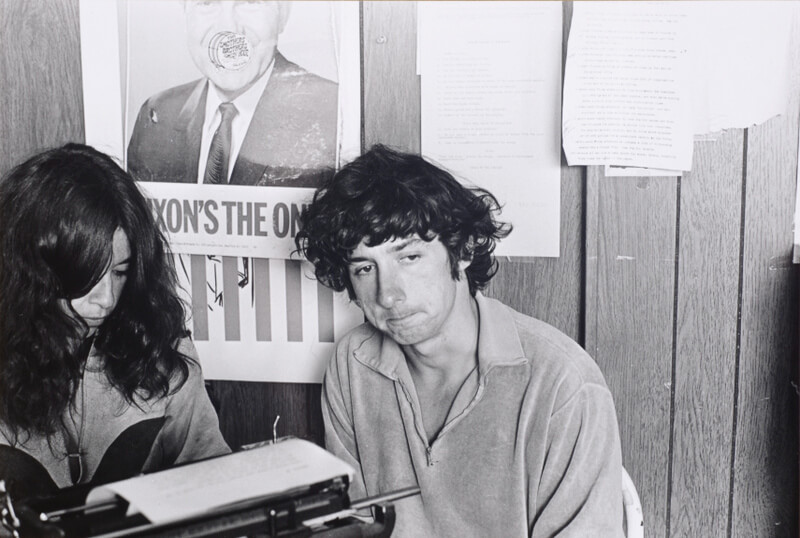

James Rector was killed at People’s Park, the artist Alan Blanchard blinded, draft resistor Gentle Waters injured with birdshot and I woke up one morning to find a bullet hole in a downstairs window of the Ashby House. With Tom’s guidance, with his leadership and his direction, again Steve, Stew, I plus others went on to organize what, with typical 1960s grandiosity, we called the International Liberation School. Our purpose was to educate and train potential revolutionaries. The ILS published pamphlets with titles such as “Firearms & Self Defense” and “Every Soldier a Shitworker, every Shitworker a Soldier.” Speaking of shitworkers, I brought with me my favorite picture that is clear, documentary evidence of our future feminist complaints about women doing shitwork for men. Here I am in 1969 typing for Tom:

To supplement our education in revolution, Tom screened his friend Robert Kramer’s movie ICE in Anne’s living room. ICE was a black and white movie shot in cinema verite style about white American guerillas, women and men, who engaged in military resistance to a dictatorial U.S. government. Although I don’t recall Tom doing this himself, I do know many of us went to the Chabot Gun Club to practice self-defense. As I said, Tom was the main mover and shaker of the Berkeley Liberation Program and the ILS; the militancy of those times was a militancy Tom shared.

By the fall of 1969, Tom, seven other defendants, and much more secondarily myself, were enmeshed in the Chicago Conspiracy Trial. Tom frequently wore a blue denim shirt to court as a to symbolize the Southern Civil Rights struggle. Tom took clear sides in the culture war that erupted over defense strategy. The Yippies: Abbie Hoffman, my and Stew’s pal Jerry Rubin and to a lesser extent Lee Weiner, argued for a countercultural spectacle, to hold the system up to ridicule. Attorney Bill Kunstler agreed. Tom, John Froines, and attorney Len Weinglass argued for a more traditional defense. Ultimately, both sides won. Stew, Rennie Davis & Dave Dellinger brokered the peace. More than one hundred witnesses took the stand inside Judge Hoffman’s courtroom which Abbie had renamed a neon oven. I don’t know the reasons Rennie was the one to testify, not Tom. In the middle of the trial, December 4th, 1969, Chicago cops murdered local Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in their sleep, prompting a 2nd rebellion by Tom and other defendants about the inhumane treatment of African Americans in Judge Hoffman’s courtroom; the first rebellion had occurred two months previously when Bobby Seale was chained and gagged so he could not act as his own attorney.

One day a clandestine message arrived at the Trial office. Representatives from North Vietnam wanted to meet the defendants in a town outside Montreal. Once again, the defendants quarreled; they fantasized about leaving the country. Saner lawyers prevailed. Crossing the Canadian border would have violated their bail. The defendants could not go. But I, the Canadian, did. My job was to represent the cultural side of the conspiracy trial culture wars, while Frank Joyce, a boyhood friend of Tom’s, represented the mainstream. As a result, I would become one of approximately 200 anti-war activists, who, like Tom was privileged to visit the former North Vietnam while the war still raged.

Thus began a life-long love affair Tom and I shared—we hated the war in Vietnam but loved the courage and dedication both of those Vietnamese revolutionaries we met personally and the entire Vietnamese people. Our mutual anti-war activism bonded us together more than any of our previous radical adventures, so much so that, when I visited Tom at his home four years ago, he gave me a statue of a Vietnamese woman that Xuan Oanh, a mutual Vietnamese friend of ours, had given him. Perhaps Tom recognized he was dying; it felt like Tom was passing on an inheritance from a dear friend we both admired. To me the statue stands for the idealism and romantic attachment many in my cohort had with Vietnam. You’ll find Tom’s description of Oanh and the statue in Hell No.

I last saw Tom in 2015 at the Vietnam: The Power of Protest Conference in Washington D.C. I found Tom a little confused and disheveled, yet still passionate in his conviction that we, the peace movement, must reclaim our history and by so doing overcome America’s refusal to admit the Vietnam War was wrong and we, the demonstrators were right.

I last saw Tom in 2015 at the Vietnam: The Power of Protest Conference in Washington D.C. I found Tom a little confused and disheveled, yet still passionate in his conviction that we, the peace movement, must reclaim our history and by so doing overcome America’s refusal to admit the Vietnam War was wrong and we, the demonstrators were right.

I want to close saying something about death. Stew passed away in 2006; he was 66, ten years younger than Tom when Tom died. 20 days before Stew died; an e-mail from Tom arrived. titled What the Hell? a play on Stew’s memoir “Who the Hell is Stew Albert.” Tom asked if Stew had received a second opinion. He ended his e-mail with: “always thinking of you, Tom.”

Grieving is not linear. Everyone grieves in her or his own way. One day, one hour, one minute you will feel one way and the next minute, hour or day — wham, you feel the opposite. There’s no predicting and certainly no control. So now Tom is gone and sadly it’s my turn to say goodbye:

“Tom – you were brilliant, irascible, loyal and strong minded, ecumenical, occasionally grumpy but very generous. I will miss your powerful intellect that covered up a heart of gold. You inspired not just me but an entire generation of rebels. You still do. And please – give my love to Stewie if you see him.”

Thank you.

Find Judy Gumbo at www.yippiegirl.com or on Facebook as Judy Gumbo Albert or Yippie Girl.