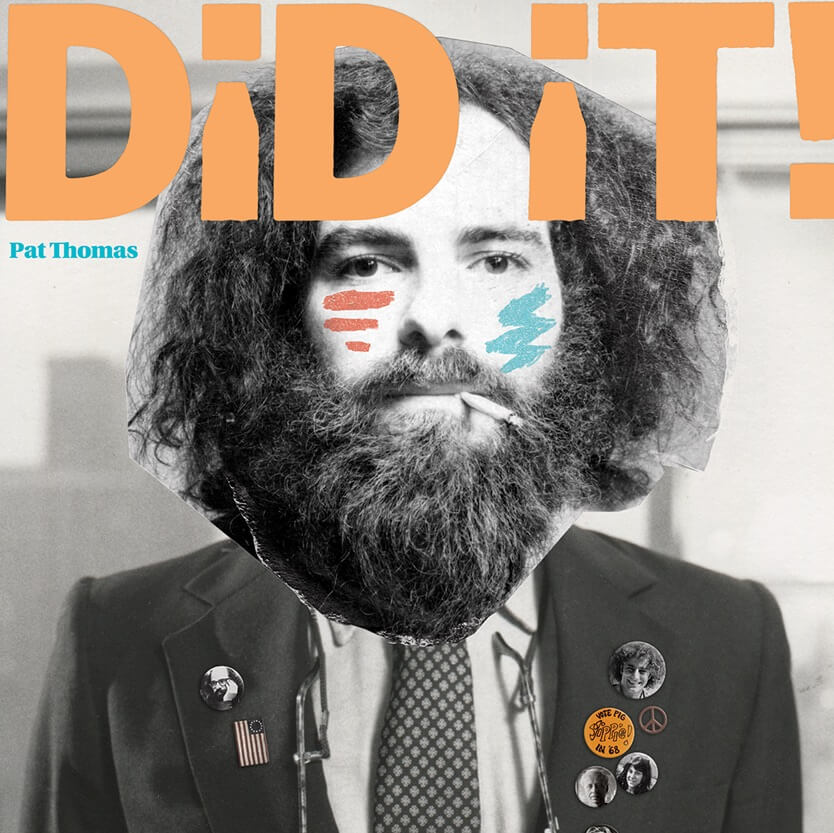

Red Diaper Yippie

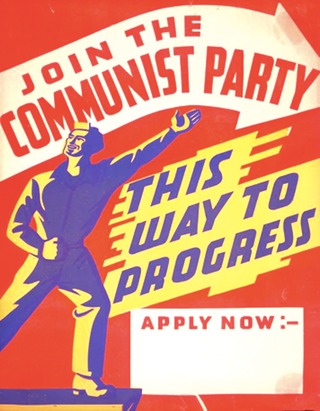

Back then, I couldn't really grasp the essence of ironic Yippie politics. What blocked me was my tendency to take everything literally; a survival mechanism, I've come to believe, left over from growing up in a Communist Party family. The world of my childhood felt highly political and very serious. I have a ten year olds' memory of picking up the yellow kitchen wall phone to call the White House and tell the operator to ask President Eisenhower not to execute the Rosenbergs. My father, Leo Clavir, was the first person to import Soviet films into the North American continent, so my formative movie experiences consisted of first run, private screenings upstairs in my grandmother's living room, of what were to me the terrifying Eisenstein classics Potemkin and Ivan the Terrible. At our dining room table I sat directly across from the family bookshelves that contained not just Marx and Lenin, but also my mother's prized volumes of Walt Whitman and John Dos Passos. Topping my list of permitted reading from these shelves was Anton Semyonovich Makarenko's leather bound, brick-red, gold and black embossed tome Road to Life, a visionary socialist saga in which young boys learn to work diligently, act responsibly and accept, for the greater good, limits on their individual rights and privileges. Comic books were forbidden because comic books were evil, as spelled out in the fear-mongering screed (also forbidden, third shelf from the top) Seduction of the Innocent. Why then can I still recall its artistic illustration of a dagger being plunged into the eye of a screaming woman? Don't ask.

Back then, I couldn't really grasp the essence of ironic Yippie politics. What blocked me was my tendency to take everything literally; a survival mechanism, I've come to believe, left over from growing up in a Communist Party family. The world of my childhood felt highly political and very serious. I have a ten year olds' memory of picking up the yellow kitchen wall phone to call the White House and tell the operator to ask President Eisenhower not to execute the Rosenbergs. My father, Leo Clavir, was the first person to import Soviet films into the North American continent, so my formative movie experiences consisted of first run, private screenings upstairs in my grandmother's living room, of what were to me the terrifying Eisenstein classics Potemkin and Ivan the Terrible. At our dining room table I sat directly across from the family bookshelves that contained not just Marx and Lenin, but also my mother's prized volumes of Walt Whitman and John Dos Passos. Topping my list of permitted reading from these shelves was Anton Semyonovich Makarenko's leather bound, brick-red, gold and black embossed tome Road to Life, a visionary socialist saga in which young boys learn to work diligently, act responsibly and accept, for the greater good, limits on their individual rights and privileges. Comic books were forbidden because comic books were evil, as spelled out in the fear-mongering screed (also forbidden, third shelf from the top) Seduction of the Innocent. Why then can I still recall its artistic illustration of a dagger being plunged into the eye of a screaming woman? Don't ask.

The Soviet Union was a dependable but not overwhelming presence in my young life. I learned to speak minimalist Russian: "zdrastvystye" (hello), "dosvedanye" (goodbye), "tovarisch" (comrade) and the memorable phrase "Sobranye nye vosim ab shest" (The meeting will be at six instead of eight.) When our dinnertime family mood was light, my parents, sister and I would begin chanting "Sobranye," and, when we got to the word "Ab" lift the dining room table a few inches off the ground then bring it down with a resounding thud on "shest." I learned internationalism or ecumenism in today's terminology, at my Jewish/commie day camp, where I, the little Dutch Girl, together with the other children dressed in native costumes from all over the world, sang together, in our high, sweet, young voices: "Arise ye prisoners of starvation, arise ye wretched of the earth." I still have faith in the elemental Red Diaper mantra I absorbed as a child: from each according to his/her ability, to each according to his/her need. You put into society what you can and you take out what you need. Simple. Equal. No distinctions based on wealth or class.

I've come to suspect that my parents must have been semi-clandestine Party members. For business purposes, it would benefit the Russians to give their North American film franchise to someone they could completely trust, but who was not publicly identified with the Party. Early on, my parents had let my younger sister and I in on the fact that they were indeed Party members; this information was not exactly secret, but it wasn't to be broadcast either. The Party was my parent's community: all their numerous close friends were in the Party; Canadian Party Chairman Tim Buck and other communist notables were frequent visitors to our home. On the occasional deep winter night, the same two short pudgy, Russian-speaking men dressed in long, heavy black wool coats and grey lambs wool hats pulled tightly over their ears, would appear on our front stoop and be long gone by the time I woke up.

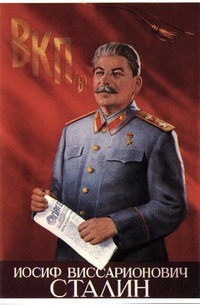

My father Leo would take pre-paid trips to Russia, ostensibly for his movie business. Harriet stayed home. "Whaddidyabringme?" were the first words out of my mouth when Leo returned with the latest in Soviet crafts as presents for his wife and daughters: large brown fur hats, bright multi-colored nested wooden figurines. I recall a peasant doll of un-Russian, Barbie-like proportions, clothed in a peasant blouse, green velvet vest skillfully embroidered skirt, and hand-made lace-up leather slippers. There was a delicately carved wooden Baba Yaga witch puppet complete with black cape, babushka and oversize yellow/grey peasant boots that my sister and I fought over for years. Leo found stamps for my collection: four-color Lenin in the snow surrounded by happy peasant children, or standing on a cliff, grey storm clouds above, red flags festooned with gold hammer and cycles below, exactly like Moses parting the waters in the Ten Commandments. I even recall a green 30 kopek Stalin stamp, with a circular drawing of the famed dictator's head and mustache superimposed on a line of eight white horses, charging forward; each horse carrying a giant socialist-realist flag waving boldly in an invisible wind. Just like my camp song predicted: "United Nations on the march with flags unfurled, together fight for victory, a free new world."

Five years before Leo died, he, Harriet, Stew, and I attended a recital in Portland where Stew and I lived. The pianist was an older, grey haired man whose name I no longer remember. Anxious and excited, my father insisted, at the end of the concert, on going up on the small stage to introduce himself, but what popped out of his mouth at the crucial moment was not the name Leo Clavir but the name Allan, a name I'd never heard him use before in my entire life.

What was that? I asked.

What was that? I asked.

My mother scowled.

My other name, my father replied. But just forget I said that, understand?

Ahhhh... the thought occurred to me as I wrote this a few days ago, Just like Stew and I were Spring and Victor to the Weather Underground.

Just forget I said that, understand?

One day the Russians arbitrarily transferred their film import franchise to the American impresario Sol Hurok. Leo went on to make and lose all his money promoting bingo games on radio and TV. Until the day he died in the late 1980s, my father defended the Soviet Union. When it collapsed, my sister and I were both very grateful that Leo was already gone.

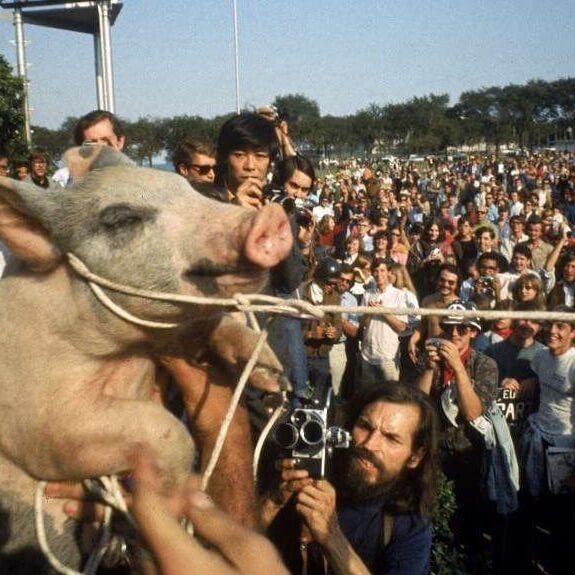

I grew up a red diaper baby. To me that meant: Work hard. Take things seriously. Be a force for good. I was a Yippie leader in the 1960s. To me that meant: Have fun. Don't take anything seriously. Be a force for good. How can I possibly integrate these two aspects of my self? In the long view of history, as my father used to say, I've learned to live my life based on the following mantra: Stalinist discipline (or SD as we call it around my house) gets the job done, but flamboyant, imaginative, over-the-top Yippie theatrics are a lot more fun.