The Chicago 7 movie and me

by Judy Gumbo

yippiegirl.com

I attended and worked at the Trial of the Chicago 7. The defendants became my friends. I think Sorkin’s movie is terrific. Here’s why: It’s a block-buster Hollywood movie in which the Yippies and the anti-war movement are portrayed as heroes.

Sorkin’s narrative focuses on conflict - between those who protest for a righteous cause and cops, Attorney General John Mitchell and the Nixon administration. Sorkin raises the racist treatment of defendant Bobby Seale, so boldly his audience is forced to pay attention. I also heard that Sorkin consulted only with the late defendant Tom Hayden. Which explains the Tom character and especially why the movie focuses on the back and forth between non-violence vs. violence – as Tom did. And as a Yippie I am especially delighted that Yippie characters and history are so prominent. It’s about time!

Yes, Sorkin does play fast and loose with facts, personalities, timeline, you name it. But movies define history. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is not a documentary; it’s that major motion picture Abbie Hoffman lusted after - and a gift to all resisters.

Here’s what I can add:

THE YIPPIES: Movie Jerry Rubin bears little to no resemblance to the Jerry I knew. Jerry was more fearful than Jerry as portrayed; he never advocated use of explosives. Nor did he have a relationship with a blond female police agent. His partner Nancy was a Yippie; she had dark curly hair; she and I went on to visit the former North Vietnam while the War still raged. We remain close friends. But Jerry did take a male agent named Robert Pierson as his bodyguard; Pierson testified against Jerry at the Trial. Jerry was a gifted grassroots organizer who became a national celebrity; he was never an actual stockbroker as the movie claims, but he did become a publicist for a socially responsible investing firm.

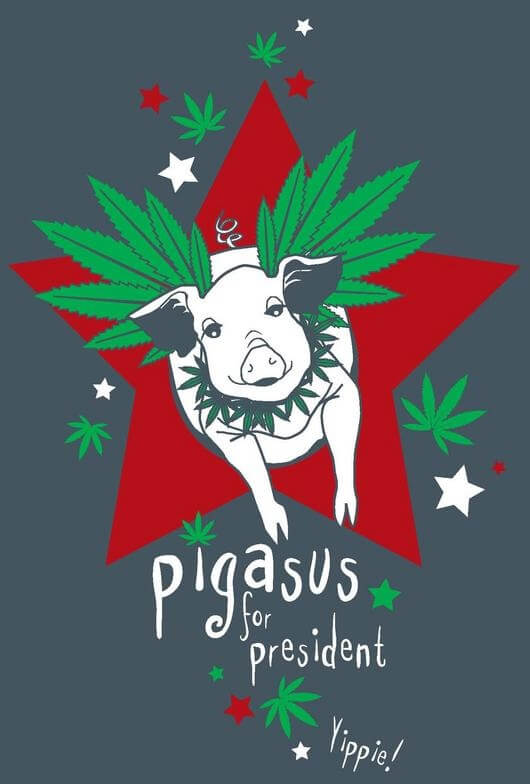

The real Abbie Hoffman was above all a performance artist – he gave stirring speeches and pulled pranks. He was a far less serious activist than how Sasha Baron Cohen portrays him. As Sorkin makes clear, Abbie did get into conflicts – but as much with Jerry as with Tom. For me a primary Abbie/Jerry conflict occurred over who got to decide the size of Pigasus, our Yippie candidate for president. Which of these two guys, Abbie or Jerry, could claim to swing a bigger Pigasus dick?

Speaking of height: it was weird to see attorney Len Weinglass portrayed as so much taller than Bill Kunstler and Abbie so much taller than Jerry. In reality, all four were Jewish guys of equal and average height.

HOW WOMEN ARE PORTRAYED: Pigasus, our Yippie presidential candidate, is consistently referred to as male. She was not. She had no large tusks. I consider her female; photos of both Jerry’s large, and Abbie’s small cute pigs reveal an indeterminate gender. But, as usual with women and transgender folks, we are ignored.

Abbie once told me I should have been indicted. No women were. In Sorkin’s Conspiracy Trial office, a tall blond woman named Bernardine answers phones and hands out mail. Which I did. She looks like Gloria Steinem. I do not. Nor was I the Weatherwoman Bernardine Dohrn. Ah well. I was in fact the “manager” of an unmanageable Trial office for a few weeks, only to be replaced by a man. I then snail-mailed transcripts of the Trial’s daily dramatics to underground and mainstream media across America and in Europe – which made it clear to me that she who disseminates history can rule worlds.

A character based on Anita Hoffman does not appear in Sorkin’s movie. In real life Anita faced the traditional, patriarchal bind of a woman married to a charismatic man. Anita and I kept a cool but friendly distance when we first met that summer of 1968, but at the Trial, I began to hear rumors: Abbie, to use the vernacular of our time, 'took advantage' of women. Frowns occupied Anita's face. Only after the rise of the women’s liberation movement did Anita and I become close. I visited Anita’s bedside shortly before she died.

Beyond Sorkin’s portrayal of a woman with an American flag (which was in fact an NLF flag to show our solidarity with South Vietnam’s liberation forces), being carried in a demo and subsequently brutalized by cops, the majority of women protesters I knew – myself included - were helpmates who supported men. No bras were burned – either in Chicago or, as myth has it, one week later at the 1968 Miss America Pageant protests. But Chicago and the Trial did give women like me a key experience of self-empowerment: I learned to stand my ground, to fight back and to resist. All of which I needed to become a free woman. At the end of the Trial, Jerry’s partner Nancy, Anita Hoffman and Dave Dellinger’s daughter Tasha, dressed as Witches, burned judge’s robes to denounce the verdict.

CULTURE WARS

Sorkin collapses the Trial’s culture wars into a single conflict: Tom vs Abbie. In reality, the late Stew Albert, my partner and unindicted co-conspirator, plus Dave Dellinger and Rennie Davis acted as go-betweens to create a politico - cultural defense. Tom, John Froines and Len Weinglass took the mainstream side; Abbie, Jerry and Bill Kunstler identified with the Yippies. In addition to prosecution witnesses, Abbie and Rennie testified for the defense along with Allan Ginsberg, singer Joni Mitchell and LSD guru Tim Leary. Equally, sympathetic lawyers and mainstream peace movement stalwarts took the stand. Ultimately both sides won: more than 100 people testified for the defense. And Dave never slugged anyone. The Chicago defendants were acquitted of conspiracy but convicted of crossing state lines to incite a riot and of contempt of court. All charges were later dropped.

JUDGE AND COURTROOM

I figured the actor Frank Langella was perfectly cast as Judge Julius Hoffman since he played Dracula in movies. Jerry and Abbie’s name for Judge Julius was not Dracula but Mr. Magoo, a Yippie sendup of the short, grumpy- old-man cartoon character who Julius Hoffman physically resembled, his bald head shaped like an egg poking over his judge's podium. But Julius Hoffman was no Yippie; he possessed an affect and a temperament more severe and racist than any late 1960s cartoon. Langella’s Hoffman wasn’t evil enough for me.

Sorkin gets Judge Hoffman’s courtroom right – and wrong. The movie shows spectators seated together but in reality, as if a hippie bride was marrying a Republican groom, marshals escorted me and other spectators to separate sides of the courtroom. I’d be seated on the right, in the second row behind the press. Hippies, Yippies and friends of the defendants piled in behind me, with defendants and lawyers in front of us at a messy table. On my left, men in suits and women in red wool dresses and high heels, supporters of the prosecution, sat closest to an elevated jury box while the two prosecution attorneys, one gray haired, the other younger, both dressed in bespoke suits, sat at their separate table; no mess in sight.

BOBBY SEALE AND FRED HAMPTON

I well remember those portraits of Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, slave-owners all, who glowered down from the courtroom’s walls. Before his case was severed, an act which turned the Chicago 8 into the Chicago 7, Bobby had pointed to these oil paintings and declared to the judge,

"What can happen to me more than what Benjamin Franklin and George Washington did to Black people in slavery? What can happen to me more than that?'

Sorkin makes it clear. In Sorkin’s movie, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II plays Bobby Seale, Kelvin Harrison Jr. plays Fred Hampton. To my knowledge Fred Hampton did not advise Bobby as the movie portrays, but I will not forget Hampton’s death. On Stew’s 30th birthday, December 4, 1969, in Chicago, Jerry, white faced and breathless, barged into Stew's and my bedroom, bellowing that we must get up immediately,