Gun Show After Tucson

Checking it out at Crossroads of the West Gun Show. Image from Spirit of the Sportsman.

Like most Americans, I've been wrestling -- no, agonizing -- about guns. Then I heard about a gun show at San Francisco's Cow Palace. So I go. To confront my inner turmoil.

Back in the late 1960's, I passionately believed the revolution had come. It was, like the Black Panthers said, time to pick up the gun. John Lennon sang sweetly in the background: "Happiness is a warm gu-hu-hun." My anti-war cohort and I went to a gun show in Contra Costa County. We bought low-end rifles, a shotgun, a handgun. We cleaned 'em. We went to the Chabot Gun Club and shot 'em. We cleaned 'em again.

My cheap .22 Italian rifle against my shoulder made me feel as powerful as Superman.

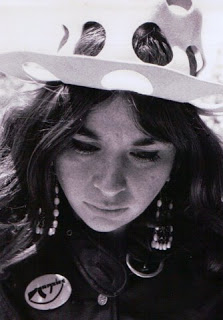

Forty years later comes Tucson. Other massacres precede it. I react with horror and empathy like the rest of the world. How do I explain my past self in the present? "You're not the Teabag Hat Lady, you have completely different moral values, an opposite worldview," I tell myself each time I see her on TV with her pals, rifles carried openly at their sides. I once loved guns. After Tucson, the duality is driving me crazy.

My first thought is: what to wear? Not my black Greek fisherman's cap with its faux diamond peace pin that I bought in Washington, D.C., at the last gigantic pro-choice rally. Not my gorgeous rust-brown Sergeant Pepper jacket with its epaulets, bronze buttons, and pearl encrusted three-inch wide pink velvet flower pin. I settle on inconspicuous: jeans, white vest and sweater, and a black, Access Capital Strategies cap. Maybe they'll mistake me for a capitalist. I reject the iPad, but worry that my recycled brown paper notepad with its peace dove and ECOHOPE cover might draw attention.

I park behind a Lexus. There's a BMW to my right, a yellow Hummer to my left, a lone green Prius sits between two black pick-ups, one of which is a Toyota. Not the America First cars I was expecting. I avoid the outdoor red, white, and blue NRA tent, pay my $10, and go inside a crowded, high-ceilinged shell. American flags are omnipresent but not intrusive. "Wow, this feels familiar," is my first reaction.

A vendor calls himself "Tactically Armed Citizen" (e-mail TGUNNUT). I stop, breathe, and then approach his stacks of two-foot long thin boxes. On top of each is a different make of rifle, most with elaborate eight-inch black scopes. The front barrel of one rests solidly on a black metal tripod. This gun could mow anything down.

A genial curly-haired white guy with wire-rimmed glasses is explaining the gun to a tall forty-something East Indian customer. Their conversation is casual, friendly, knowledgeable; I pick up no hint of prejudice or fear. The price tag is $1,750. The gun looks heavy. But not larger than life, like in the movies.

"What's this gun for?" I ask, running my fingers down a sleek black barrel.

"Hunting. Target practice."

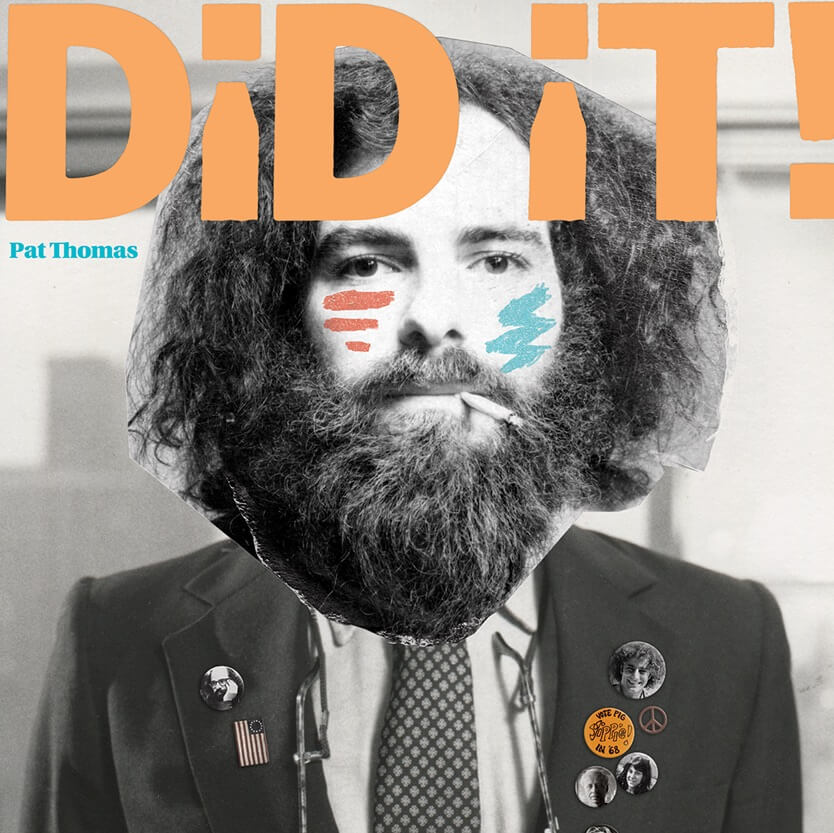

Gun-packing mama? Judy Gumbo Albert, in the day.

I realize that, to work things through, my former gun-loving Judy Gumbo persona needs a voice:

"I'm looking for something for self defense."

"Self-defense? You need a handgun."

"No," I reply, "I've never liked handguns. Too hard to aim."

"How about a shotgun?" he suggests.

"Nahh, too much kick." The ease with which my minimal knowledge comes back surprises me.

Gun vendors are outnumbered by people selling peripherals: green, orange, and camouflage hunters' vests; scary looking gun stocks made of lightweight black metal; high strength instant glue; carefully arranged antique and modern military medals in glass-covered display cases; multiple varieties of beef jerky. Vicious hunting knives sit alongside multicolored switchblades.

I see tables covered with sexy curved black magazine clips that, no matter how large they look, are, I'm assured, jiggered to hold California's legal limit of 10 bullets. The ammo section is conspicuously bare of product. I'd read there'd been a run on bullets since Tucson, fear of increased restrictions.

I feel bizarrely at home in this multi-aged crowd of beer-bellied white guys, short Spanish-speaking men, young hand-holding couples, Asians, Savage Breed motorcyclists, women pushing strollers. I'm just another Grannie looking to defend herself. The t-shirt on a passerby reads: 'If you know how many guns you have, you don't have enough."

I make my way past a vendor who has lethal looking sleek black military-style firearms for sale. His logo is a target. His guns are made in the USA. And Russia. Of airplane grade aluminum. One has a 10" long calibrated sight he says is accurate up to 1,000 feet.

"What's this gun for?

"Target practice."

"You need a guy like Castro to take over." I overhear a longhaired fifty-something vendor trying to talk a group of Chicano men into buying Stetsons. "Make the rich leave. Give the country to the people." This man wears a Superman t-shirt. A familiar "what else is nu?" gesture accompanies his New York salesperson prose. I wonder if I've found a landsman.

In addition to Stetsons, rifles, and handguns he sells hemp bags with images of Pancho Villa. He says the Mormons who run the gun show won't let him sell his smoking paraphernalia. He tells me a friend in Kingman, Arizona, owns a gun safe that takes up an entire wall. "He comes home at night, opens it, sits in front of it and stares. He isn't married."

"What does he do with all those guns?"

"Target practice."

I visualize millions of bullets whipping across American farmland, or burying themselves deep into targets at gun clubs and ask myself what violent fantasies lie beneath the meaning of the phrase: target practice.

Then I see it. A small, Judy Gumbo kind of gun. Black. Maybe one and a half feet long. Curvaceous clip. The gun calls to me like that slouchy, punky teenage boyfriend my parents hated.

"It's an AK 47 pattern pistol," says Mark, the young vendor with twinkling dark eyes. He's either impossibly earnest or flirting with me.

"It looks like a rifle, but it's a handgun. It's sold to shoot only one bullet at a time, but you can legally convert it to semi-automatic."

"How fast will it shoot?" I ask, lusting in my heart.

"As fast as you can pull the trigger," he replies. Mark tells me it's legal to own a machine gun in 33 states.

Uncle Sam Bank. Image from What's it Worth.

I pick the gun up. I nestle it into my left shoulder blade. Wrong. I'm right-handed. I change hands, balance the gun in my left hand and place my right finger on the trigger. "Nah," Mark says, "Hold it straight out in front of you. It shoots like a pistol."

"How much?"

"$829.00"

"What do you use this kind of gun for?"

"Target practice."

"Thanks," I tell Mark. "I need to think about it."

On my way out, I spot an Uncle Sam Bank. It's 11 inches tall, made of cast iron with "BANK" painted in gold on all four sides of a red base. Uncle Sam stands erect. He wears black tails, striped white pants and a blue top hat with stars. You put a coin in his metal hand, press a metal nail and '"fwump," the coin ends up in a red suitcase that, if it weren't metal, could double for a carpet bag.

I disdained such items in the 1970s as patriotic artifacts of the war-mongering ruling class. In 2011, I buy it for $20. Given the financial crisis, bank bailouts, and profit-seeking patriotism of the arms industry, an Uncle Sam Bank feels like the perfect gun show souvenir.

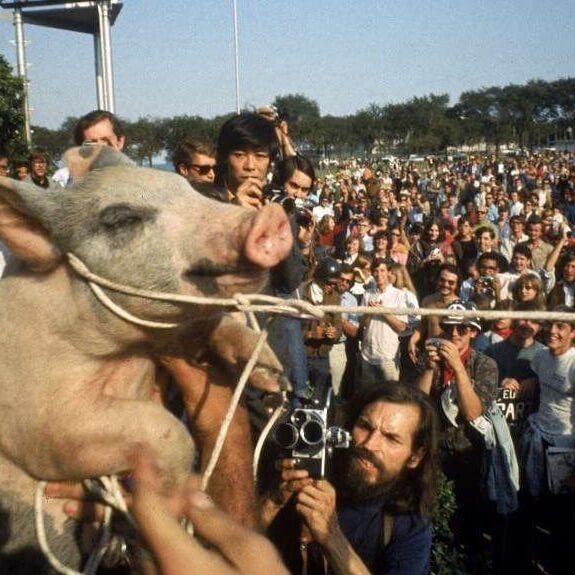

I was 26 years old in 1968. I'd not yet experienced the death of a loved one or the birth of a child. My late husband Stew Albert and I, the late Abbie and the late Anita Hoffman, the late Jerry Rubin and Nancy Kurshan, plus a few thousand fellow Yippies, coughed our lungs out in Chicago from acrid tear gas lobbed at us for protesting the Vietnam War at the Democratic National Convention.

The following year, in that same city, Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were murdered in their beds. This reality gave birth to my gun fantasies; yet I never used my gun against a living being. Our movement managed, without assault weapons, to end a war and help change lives of people struggling for equality and justice.

Today I wish I had a magic bullet to stop gun violence. And I worry about the big-bellied men I saw at the gun show who claim semi-automatic weapons are just for target practice. It seems obvious to me that their ultra-right-wing fantasies are closer to becoming real than my youthful Yippie romanticism ever was.

I departed the gun show at peace with my past, but very much aware it felt like Tucson never happened.

Judy Gumbo Albert is completing Yippie Girl, an insider's memoir of love and friendship among the Yippies and other romantic revolutionaries of the late 1960s. In addition to publishing two books, her work has appeared on CounterPunch, and The Rag Blog. Contact her on Facebook or at her website, www.yippiegirl.com.