Brave New Life: How Stew and I Met

At the time the Oakland 7 were arrested and charged with attempting to shut down the Oakland Induction Center, I still lived in my hometown of Toronto, Ontario Canada. America was at war with the tiny nation of Vietnam. Draft-age men were fleeing the States to come and live in my home country. I believed passionately that the war was wrong, but my experience of demonstrations was limited to marching in peaceful protest with my first husband outside the US embassy in Toronto demanding an end to "Canadian Complicity in the Vietnam War." The slogan End Canadian Complicity represented everything about Canada that had motivated me to leave: Boring. Too far removed from the action. Not out front. Not direct. Not like STOP THE DRAFT! Not like PEACE NOW!

At the time the Oakland 7 were arrested and charged with attempting to shut down the Oakland Induction Center, I still lived in my hometown of Toronto, Ontario Canada. America was at war with the tiny nation of Vietnam. Draft-age men were fleeing the States to come and live in my home country. I believed passionately that the war was wrong, but my experience of demonstrations was limited to marching in peaceful protest with my first husband outside the US embassy in Toronto demanding an end to "Canadian Complicity in the Vietnam War." The slogan End Canadian Complicity represented everything about Canada that had motivated me to leave: Boring. Too far removed from the action. Not out front. Not direct. Not like STOP THE DRAFT! Not like PEACE NOW!

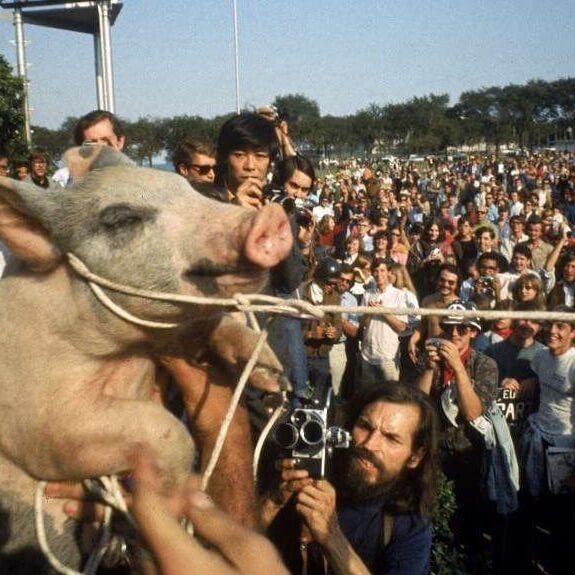

I moved to Berkeley from Canada in late 1967, hungry to explore my brave new world. Apart from my roommates on Keith Street, I knew only one other person in town. A rally for the Oakland 7 would, I figured, be a lot more exciting place to meet people than outside a US embassy in stuffy old Toronto.

I dressed carefully for the event in black fishnet stockings, high brown leather boots, and my favorite light brown suede miniskirt that matched my hair. My mother gets all the credit for my fashion sense. When my father Leo Clavir met Harriet Kamman at a Communist Party meeting in Toronto in the early 1930s, Harriet was a slim, attractive blonde, blue-eyed beauty - well before 1956, when she quit the Party, escalated her drinking, put on all that weight and froze her mouth in a severe, disapproving, upside down U. Harriet had imbued in me the notion, popular among Toronto anglophiles, that whenever you go out in public you dress your very best. You hold your head high. You are, after all, a proud subject of Her Majesty the Queen.

Now Dorothy from Canada found herself in Oz, or perhaps I'd fallen down Alice's rabbit hole. I stopped at the entrance to a large room which was jam packed with tables; every surface covered with unruly stacks of newsprint and brightly colored leaflets from a cornucopia of political groups. Students and non-students, protestors and faculty all crowded together; the men wearing buttoned down shirts or sexy green army jackets; tall, blonde, tanned and beautiful California girls, breasts bursting out of whatever was (or wasn't) holding them down, came right out of a Beach Boys song. It felt like a pre-Internet, anti-war Match.com.

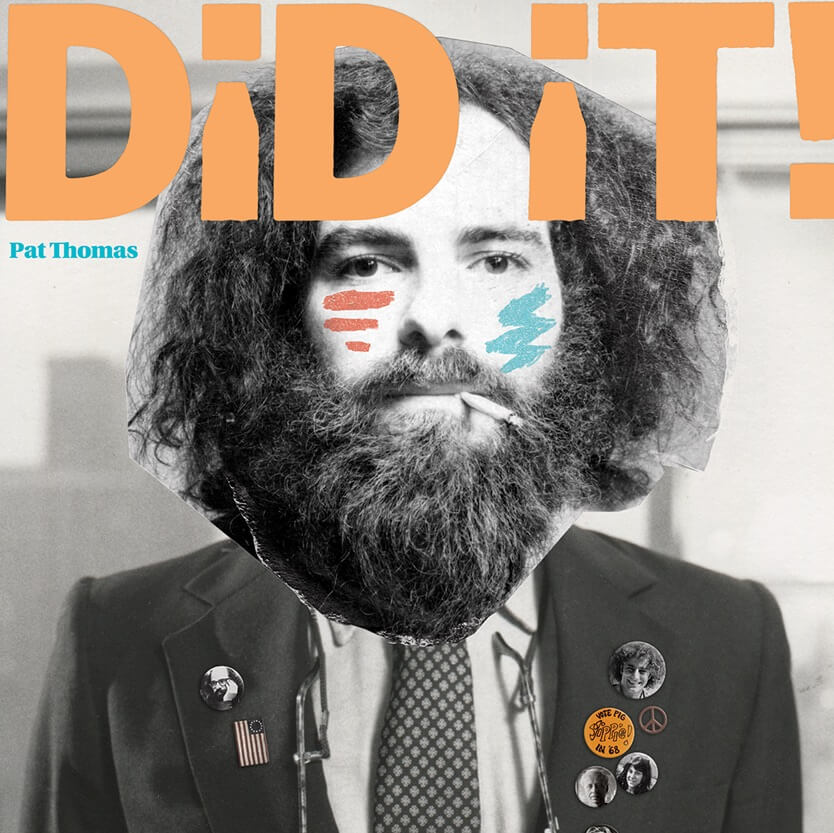

By now, my memory of what occurred next has transformed itself into pure Hollywood fantasy. I noticed one attractive young man, his face framed by curly blonde hair, wearing a faded yellow and red Indian paisley shirt and tall, fringed brown suede boots, backlit, or so my mind reconstructs, by a multi-colored California version of the Northern Lights. Dylan's Masters of War plays in the background. This man stands next to another equally attractive man, who has straight blonde hair, and is dressed more conservatively-- which wasn't difficult -- in a white shirt and tie. A two-fer of blondes! I felt like I'd died and gone to heaven. In that moment, California truly lived up to its well-deserved reputation for abundance.

I approached the guys and introduced myself, mumbling something about being a Canadian newly arrived in town. In tandem, the boys looked me up and down. "Stew" - said the curly haired one.

"Steve" - said the one with straight hair.

Then Stew reached out his long right arm and touched me gently on the tip of my nose with his little finger.

This gesture, so neutral and yet so intimate, sealed the deal. A few days later Stew and I sat together in a secluded campus grove by Strawberry Creek, shielded by towering eucalyptus trees whose leaves gave off a menthol-like sweetness, far more exotic than the acrid pine cones of my youth.

'So, ahhhh.. what brings you to Berkeley?; Stew asked.

"Politics. It's so exciting here. And... uh... well.. I was married to this guy in Canada, David Hemblen. David was Scottish and British. Very formal. Anyway, we broke up. About a year and a half ago..."

An image of David Hemblen's flat face, blonde hair and little piggy blue eyes intruded for a moment into my consciousness. I was 21 when we married. Our wedding could have been written as a script for the TV Show Mad Men. Nothing was too good for my father's eldest daughter; so much the better if the wedding could also be a business opportunity. In deference to his new in-laws my father rented a bagpiper; he impressed his cronies in the movie industry by hiring a film crew. It pains me to say that I've never been able to fully forgive my mother for spending more on her green velvet jewel-bedecked outfit than she allowed me spend on my plain, white organza wedding dress. Or on my bridesmaid's truly atrocious green sateen gowns. Two things from that marriage remain: 10 full place settings of exquisite, expensive, black, white and gold Wedgewood china, and the lesson, passed on to my daughter Jessica, that it's better to skip that first marriage completely and go directly to your one true love. Which, I'm delighted to say, Jessica did.

I used to be married too, Stew spoke in a low, intense voice. Her name was Joanne. Joanne Wyler - a California girl if I ever met one.

I came home one afternoon and found my husband in our bed with another woman. It surprised me that I could so easily blurt out my secret shame to a man I barely knew. I still felt victimized by that act: wronged, powerless, angry, betrayed -- all at the same time.

"My wife, Joanne, she just called me. On the phone. I'd asked her to come with me to work on the Pentagon demonstration. She told me she wasn't coming. She didn't want to be in New York. She didn't want to live with me any more. She didn't want to be married. She didn't want to leave California and be a revolutionary. And she said I couldn't make her. She told me our marriage was over. Just like that. Over the phone."

Suddenly my failed first marriage didn't feel quite so terrible. Stew and I had something more in common beyond our mutual sexual energy and love of radical politics. And for Stew, for the remainder of his life, he never gave bad news over the phone. If he were alive today, he wouldn't text or tweet bad news either. If you needed to tell someone something terrible, according to Stew, it was your obligation as a moral human being to do so in person.

At the end of our afternoon in the Eucalyptus grove, Stew turned, looked at me with those intense blue eyes of his and said, "You're pretty cute, you know." My heart went fulllupp. It felt perfectly reasonable to invite him back to Keith Street. I recall waiting expectantly but with some trepidation as Stew took off his fringed leather boots and unbuttoned his paisley shirt. Then we climbed together up the ladder into my six-foot high bed, me first, him following. And so began our 40 year relationship.

Shortly after Stew and I become an item, and thanks to the brilliant legal maneuverings of the well-known San Francisco attorney Charles R. Garry, the Oakland 7 were acquitted with Steve Hamilton, the other attractive blonde, among them. Some years later, Steve realized he was gay and came out of the closet -- which, given his traditional blue-collar background and the macho maleness of that moment, was very difficult for him. Stew, Steve and I remained lifelong friends. Three years and one day after Stew's death, Steve was felled by a massive heart attack. In the grand karmic scheme of things, I've always been grateful that my quest for true love led me to choose Stew. And I bet Steve was too.