Whatever happened to those radical boomer activists from the '60s and '70s?

by James Sullivan

Originally appeared in the Boston Globe

TOM WOLFE FAMOUSLY TAGGED the 1970s the “Me Decade.” The era marked the coming of age of the baby boomers, who had been outraged students in the late 1960s: for civil rights and feminism, against the war in Vietnam and police brutality. When the world didn’t change fast enough, they sought personal gain and fulfillment instead. The “Me Generation” gorged on the most prosperous period in American history and left a mess for subsequent generations to clean up. Over time they’ve become the “worst generation,” even a “generation of sociopaths.”

Or so we’ve been told.

That’s a little harsh, say those who lived it. The “leading edge” boomers — those born between 1946 and 1955 — grew up with regular reminders of the existential threats that lurked beyond the cul-de-sac: “duck-and-cover” drills in case of nuclear attack, a president assassinated for the first time since 1901, civil rights protests and race rioting, and escalating involvement in Vietnam. Then came 1968. The year had just begun when the Tet Offensive, North Vietnam’s massive effort to inspire rebellion among the South Vietnamese and encourage the United States to scale back its involvement, launched on the Vietnamese new year in late January.

Lew Finfer was a high school senior in suburban New York in the spring of 1968, organizing marchers for Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign. For him, the reports out of Vietnam that year put the lie to “three things a lot of the boomers were raised with: that our government always tells the truth, that whenever we fight a war we’re completely right and moral, and that the communists are the evil, godless ones.” Finfer never stopped organizing, moving on to school desegregation in Boston in the 1970s. Today, at 67, he serves as co-director of Massachusetts Communities Action Network in Dorchester.

“There’s a certain mythology that the boomers gave up on their idealism,” says Allen Young, who was a staff member of the Liberation News Service, the “underground” news organization founded in Washington, D.C., in 1967 by Amherst College grad Marshall Bloom and Boston University alum Ray Mungo. Like Finfer, Young, who was born in 1941, begs to differ with that assessment. “I know a number of people who became nurses, doctors, social workers, and therapists,” he says. Even many of the lawyers he knew ended up working on social and environmental issues.

In truth, most boomers did not join protests against Vietnam or anything else. The ’60s did see rallies of sizes unprecedented at the time, with 250,000 people attending the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, and by some estimates 2 million turning out nationwide for 1969’s first Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam (100,000 came to Boston Common). Relative to the population, the moratorium was probably the biggest protest the country had seen before last year’s Women’s Marches, which drew as many as 5 million Americans. The perception of the boomers as activists extraordinaire lingers, however, perhaps because they were the first generation whose iconic events were widely broadcast on television. Certainly, Doonesbury’s Zonker, Megaphone Mark, Joanie, and the rest of Garry Trudeau’s original Walden Commune residents have kept the cartoon archetypes of the boomers in the public eye.

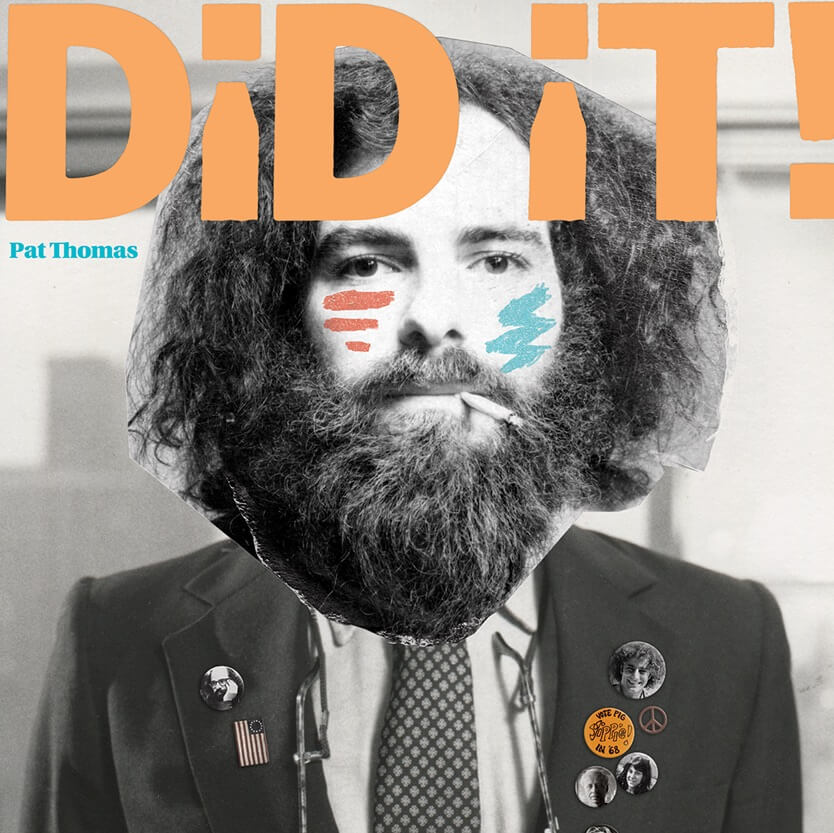

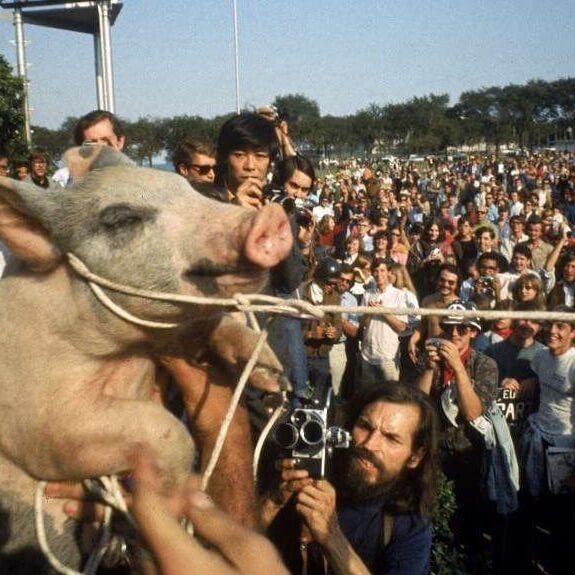

One big spark for the era’s activism was the Democratic National Convention in August 1968 in Chicago, where antiwar Senator Eugene McCarthy faced off against Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Tens of thousands of student protesters gathered on the city’s streets to demonstrate against the war. Many of them had responded to the call of organizers including the Yippies, the Youth International Party, founded by Worcester’s Abbie Hoffman and friends. The Yippies were notorious for pranks that included dumping fistfuls of money onto the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange and promising to “levitate” the Pentagon. In Chicago, they would nominate a pig as their party’s presidential candidate. But they were also savvy manipulators of the still relatively new medium of television, and effective organizers.

“There was an incredible feeling there was going to be something happening” in Chicago, says Ron Pownall, now a Boston-based rock photographer, then a college student covering the protests as a cub photographer for the Chicago Tribune. “The tension was palpable.”

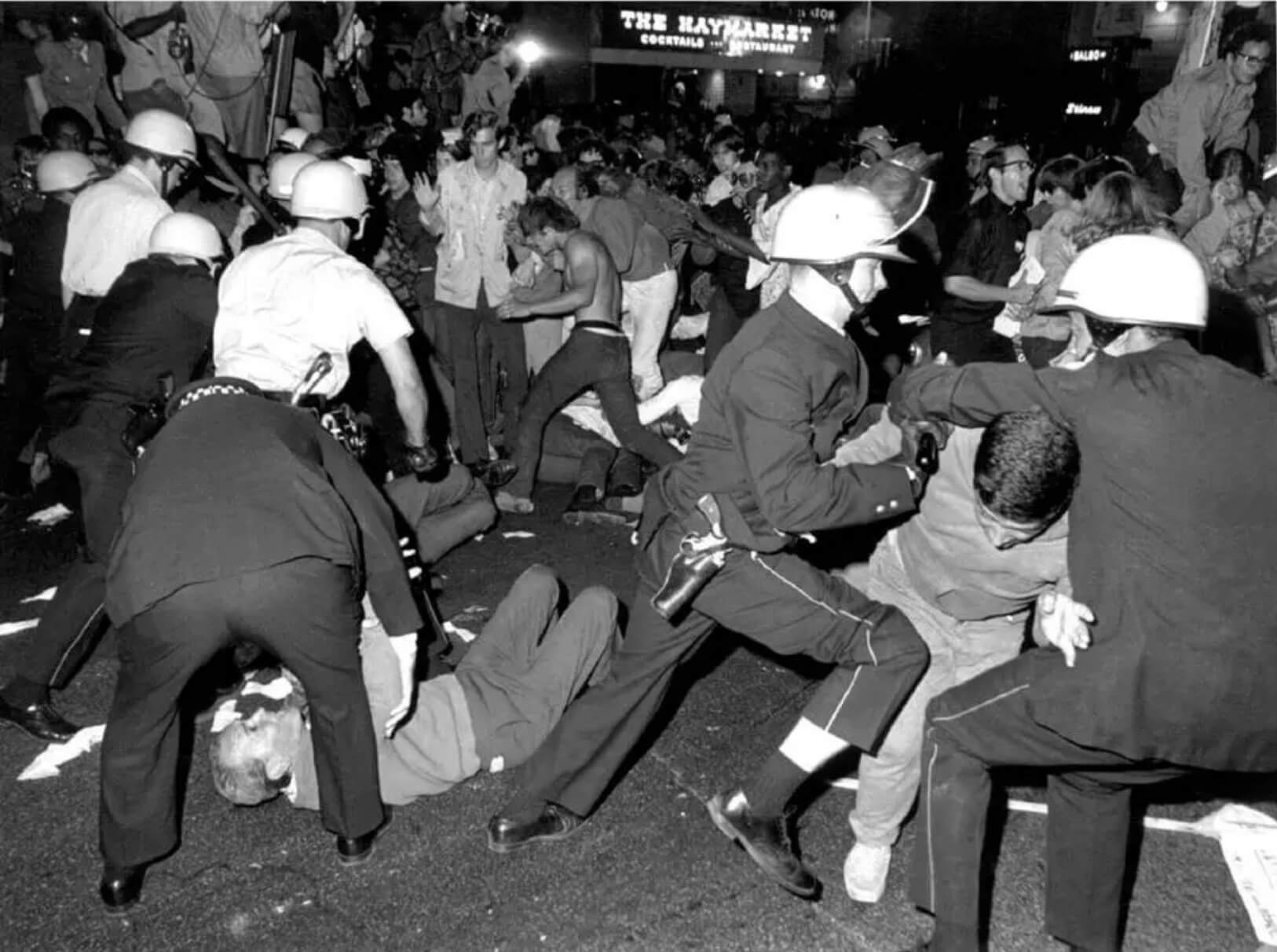

Christopher “Kit” Binns drove his Volkswagen Beetle from Princeton, where he was a student, to Chicago to support McCarthy. He found himself in the middle of the so-called Battle of Michigan Avenue. Binns, a South Shore native who is now a 71-year-old retiree living in Dorchester, remembers how the police began charging the crowd “like fish through the sea. They just kind of barged around like that all evening long.”

Pownall’s photos told the story as it unfolded, from the rows of helmeted police forming a human wall to the young man who was pummeled for pulling down an American flag. One image captures a bloodied protester on the ground, glasses in hand, while others tend to his injuries. Pownall learned months later that the injured man was Rennie Davis, another Yippie and one of eight protest organizers, including Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, who would be tried for incitement to riot in the infamous Chicago Seven trial of 1969. (The eighth, Bobby Seale, was tried separately.) An independent report pinned the violence on a minority of officers who engaged in what “can only be termed a police riot.”

Televised nightly on the network news, the footage of Chicago police clubbing and tear-gassing young demonstrators revealed two Americas, literally lined up in opposition. There were the youth, who were being sent overseas to a war they did not support, and the authorities, many of them — such as Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and FBI head J. Edgar Hoover — men who had lived through the Great Depression, men who would not tolerate dissent. “I do remember Walter Cronkite looking straight into the camera with his tortoiseshell glasses,” says Judy Gumbo, who was a leader of the Yippies along with her late husband, Stew Albert. She recalls Cronkite commenting, “ ‘They’re beating our children.’ ”

At one point, as police were herding protesters into police wagons, the crowd began chanting, “The whole world is watching.”

“We knew it was true,” says Gumbo, “and it gave us confidence. We knew we were on the side of the righteous.” During the primaries, a majority of votes cast had been for antiwar candidates. But most delegates were assigned in party caucuses, and the Democrats nominated Humphrey to run against Richard Nixon.

After Chicago, boomers and their slightly older counterparts ramped up their demands for attention. Across Greater Boston, students seemed to be out in the streets as often as they were in the classroom. Campus buildings were occupied by students at Harvard, Boston University, and Boston College, where African-American students aired a list of grievances, bringing the aims of the Black Power movement to Chestnut Hill. At MIT, students engaged in a six-day standoff with officials in late fall 1968 when they created a “sanctuary” for a soldier who had deserted after turning against the war.

MIT student George Katsiaficas was the son of an Army man; he’d been considering military service himself until the war changed his mind. He was the only undergraduate MIT named to a blue-ribbon panel to evaluate the school’s innocuously named Instrumentation Laboratory, which researched technologies for NASA and the US Department of Defense. “It opened my eyes,” says Katsiaficas. “I had no idea that MIT was so directly involved in developing weapons systems.”

The research center was eventually spun off from the school as the independent nonprofit Draper Laboratory. Katsiaficas became an ardent protester, spurred both by his work on the panel and the death of a lacrosse teammate, Paul Baker, who’d joined the Marines and was killed in Quang Tri. Katsiaficas missed his graduation while serving a 45-day sentence at the Middlesex House of Correction in Billerica for “disturbing a school.” In graduate school at the University of California at San Diego, he studied with radical Marxist Herbert Marcuse, then came back to Boston to teach social science at the Wentworth Institute of Technology, publishing more than a dozen books on leftist politics. His next, The Global Imagination of 1968, is out next month.

“Even for people who were not against the war, those events revealed the character of the world,” says Katsiaficas. “Something about the world and the way it was perceived changed. . . . The United States I thought I knew was not the United States that existed. I was totally shocked, surprised, and horrified at what was on the evening news every night.”

The unrest continued into the early 1970s. BU even canceled undergraduate finals and commencement in 1970, after a rash of fires set in school buildings. Violence created a rift between protesters who shunned aggression and those who believed it necessary for true change. Surveys have shown that protests, for all their drama, were supported by a small percentage of Americans, and they began to die down. The draft, a hot-button issue for activists, ended in 1973, and boomer activism began to shift to the Equal Rights Amendment, while the country as a whole was buffeted by the oil crisis and then stagflation. Some of the Yippies became Yuppies in the go-go 1980s — Jerry Rubin famously became a stockbroker. But Rubin also marketed a health drink made with bee pollen, ginseng, and kelp. It was called Wow!

Pownall thinks the number of boomers “who went that way, to the money side, is way less percentage-wise than it had been in previous generations. There were still a lot of people with liberal cred.” In fact, polls have shown that older boomers have consistently leaned Democrat, while those born after the mid-1950s, coming of age during the Carter and Reagan presidencies, have tended to be more conservative.

Yet even on campus in the 1960s, the boomers weren’t uniformly hippie. Reid Ashe covered the soldier-sanctuary incident as a reporter for MIT’s student newspaper, The Tech. Ashe, a native of Charlotte, North Carolina, only attended protests as a reporter. “I certainly believed that the war was wrong, that things needed to change,” he says. But while some students “were committed to the movement,” of the students he knew at MIT, many more “were too busy doing other stuff, studying for the next exam.” Ashe became a managing editor at The Tech and then went into newspaper management.

He witnessed another side of boomer activism as president and publisher of The Wichita Eagle in Kansas in 1991, when the “Summer of Mercy” took over the city for six weeks of protests against three abortion clinics. Thousands of advocates on both sides showed up on the streets; by the end, more than 2,500 demonstrators were arrested. It was one example of conservative boomers adopting the language and tactics of social protest associated with their more liberal peers.

There was no single response to the events of the times, says Theda Skocpol, a professor of government and sociology at Harvard. She and her husband, Bill Skocpol, had married as students at Michigan State University and came to Cambridge in 1969 to do graduate work at Harvard. “People took different lessons from it all. For me, all those events cemented a lifelong commitment to social justice.”

She does think the ’60s and ’70s were a freer time for activism. “People were not as fearful then as they are now,” she says. “The atmosphere of students being afraid for their futures if they got involved in protest, that was not then.”

Some members of the generation have revisited their youthful spirit of protest since fellow boomer Donald Trump was elected president. They’ve been outspoken on Black Lives Matter and the #MeToo movement, and shown up for the Women’s Marches, where thousands of boomer women joined their younger counterparts in donning pink “pussy hats.”

Boomers are supporting younger activists now. As Finfer sees it, these new generations are carrying on the healthy brand of skepticism the boomers introduced into the national discourse. Ask anyone from subsequent generations if they ever believed their government would always tell the truth, he says, “and they’ll look at you like, ‘Are you kidding?’ ”

In this new age of division and despair, Finfer still sees plenty of reasons to be hopeful. He points, for example, to the young people pushing for gun control laws in the aftermath of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shootings in Florida. It may be years before those young activists see any results, he says. “It’s not like they’re going to demonstrate every day forever. But that’s a major event some of them are passing through, the same way our generation had to deal with the Vietnam War and civil rights and so forth.

“Every generation has its idealism and people who live that in lots of ways, and obviously some people who fall short of that in lots of ways,” he says. “It shouldn’t be a choice between Mother Teresa and Jerry Rubin. There’s a lot of space in between.”

James Sullivan is a frequent contributor to the Boston Globe. His book about protest music, “Which Side Are You On?,” comes out in December. Send comments to magazine@globe.com.