My Body. My Story.

Flowers outside the Women's Health Care Services abortion clinic,

scene of the murder of Dr. George Tiller on May 31, 2009, in Wichita, Kansas.

Photo by Kelly Glasscock / Reuters.

We can't bring back the murdered physicians and clinic staff, but raising our collective voices in protest by telling our personal abortion stories is, in my opinion, a very appropriate way to honor their memories.

Talk show host Rachel Maddow recently called on the forty-five million American women who've had abortions to speak out, in response to the murder of abortion care provider Dr. George Tiller. I'm very grateful to be among that forty-five million, so, Rachel, here is my abortion story. But I wouldn't criticize any woman for dealing with her unintended pregnancy differently than I did. It is, after all, your choice.

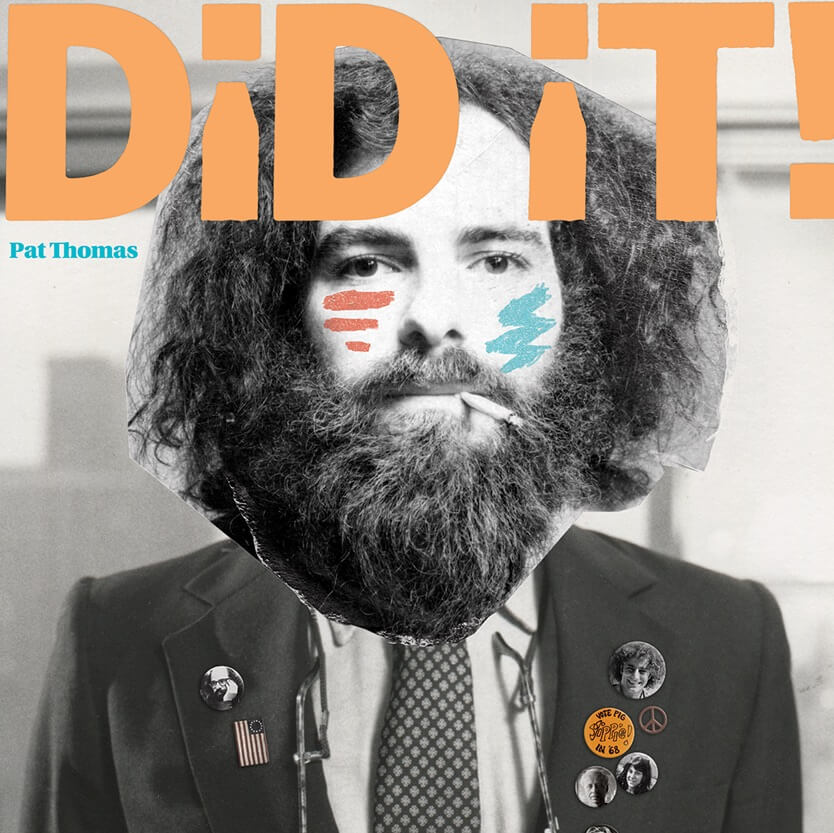

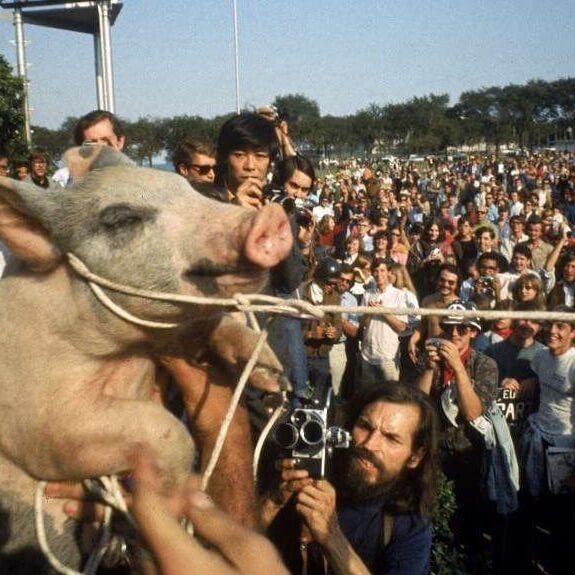

By the spring of 1972, I'd become a leader of the countercultural group known as the Yippies. I'd dedicated my life to ending the war in Vietnam and had just arrived in San Diego, to organize anti-war protests at the upcoming Republican National Convention. By then, more than 50,000 American lives had been sacrificed and more than 3,000,000 Indochinese -- including women and children -- had been poisoned, burned, maimed or killed. Yet the war raged on. It would take three more years of intense bombing of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, continued resistance on the ground combined with increasingly violent demonstrations at home, for the Nixon Administration to finally admit defeat.

By the time I arrived in San Diego, one member of an anti-war collective had already been wounded by a "stray" bullet of unknown origin. Shortly thereafter, the Republican Convention was moved across the continent to Miami, to escape a corruption scandal involving ITT (later to be absorbed by AT&T) and the Republican National Committee. Naturally, we Yippies claimed the move was prompted by fear of our planned protest activities.

Among the protestors was a 40-something older peace activist, Reverend M. P. Reverend M. was a short, wiry, nice-looking, smart man, with curly gray hair. Born a Jew, he'd rejected Judaism, spent 18 years as a Benedictine monk and had been ordained a priest. By the time I met him, he'd left the Benedictines to become a full-time organizer for one of the anti-war movement's many pacifist religious peace groups. And, after all those celibate years, he was also pretty horny. The electricity between us felt mutual; it was easy to begin a casual affair.

One morning, I woke up feeling nauseated. My stomach heaved. I could taste bile at the back of my throat. In less than an hour, the nausea passed, I was able to function, but next morning it came back. As it did every morning for a week. This could not be the flu. Finally, it dawned on me that I must be pregnant. My first thought was to blame myself -- how could I, a Yippie and a feminist, have failed to take the right precautions? And to have as the father a lapsed Jew who became a monk, was ordained a priest and then left the Church. This was not a joke or Yippie put-on.

Next, my mind jumped to the horror story my former boyfriend, Yippie leader Stew Albert, had told me a few years earlier. In the early 1960s, Stew and his about-to-be first wife Joanne, had travelled to Tijuana for a "back alley" abortion. The procedure room was tiny, cramped and dirty. Instruments lay uncovered on a dingy wooden side table. Stew had to wait outside while Joanne screamed. Back home in Berkeley, a few days later, Joanne developed a high fever; for days they both feared she would die.

By 1972, even in San Diego, that staunchest of Republican cities, abortion wasn't yet legal, but it was reasonably safe and available. I needed only to ask the women in the local San Diego movement network. The moment I grasped this, my panic ebbed and my heart rate returned to normal. I'm no bionic woman, I'd never had an abortion; so I got a little nervous thinking about the procedure itself, but since I figured I was, at the most, three weeks along, I wasn't especially worried or scared about what I was about to do. My choice was clear. And, because I felt so personally committed to being in control of the decisions that affected my life, I didn't feel obligated to consult the father in advance.

I made my appointment at the clinic recommended by my friends, and drove there on my own. The one story, light brown Spanish–style building was located on a wide, not too busy, palm-tree lined San Diego Street. The inside was painted dark olive green, with off-black, cleanly polished tile floors.

The only other person in the waiting area was a young female receptionist who sat behind an old, battered, green and gun-metal grey desk. I paid her thirty dollars -- a substantial sum for me in those days -- and she led me into a small yellow green room, with a few tiny windows close to the ceiling and bare, lights buzzing overhead. There's enough room for little more than the gurney. I took off my torn jeans and black canvas sandals, climbed up on the gurney, put my feet in the cold steel stirrups, scrunched my butt down because I'm so short, and stretched my knees as far apart as I could. This really won't hurt too much," said the young woman. "Yeah, right," I think to myself. I'm given no painkillers or sedatives.

The physician enters. I assume he is a doctor only because he wears a white coat. But he could be anybody. He doesn't introduce himself. Instead, he just starts up a loud, whirring machine that I can't see from my prone position, and, with a quick not-especially gentle motion, sticks a long cold suction probe deep into my uterus. The pain is immediate, sharp and deep. He stops. Then he begins again, once, twice, "Fuck, Fuck, Fuck." I scream. After a few more agonizing spasms "it" is gone. The entire process takes no more than ten minutes.

I always thought of "it" as protoplasm, cells accidentally brought together because I likely had neglected to take my pills. I never considered those cells to be a fetus, much less a potential human being. The concept of "fetus as baby" had not yet become part of the public dialogue. Abortion wasn't talked about publicly as murder. I had never seen a truck covered with pictures of bloody dismembered fetuses -- unlike my 32 year old daughter who surprised me recently by confiding that, when she was a teenager in her Portland, Oregon public high school health class, she was shown videos and hundreds upon hundreds of photos of, as she puts it, "chopped up fetuses and screaming women."

In that year before Roe, for me and for a very large number of American women, having an abortion wasn't a sin, it wasn't a crime -- and it wasn't a baby.

As soon as I left the clinic, my nausea evaporated. It was that quick. I felt exhilarated. My entire body relaxed, my hormones met up with my endorphins and went on a rampage, filling me with joy, energy and a profound sense of relief. I jumped into Lindequist, my 1968 dark blue VW Beetle, and made an illegal U turn across four lanes of traffic in front of the clinic. A waiting cop gave me a ticket. I didn't care, the ticket felt meaningless; getting my body and life back was momentous. I was no longer among those women who'd been held back and held down for so long. When Roe was made law the following year, my generation of women gained a new sense of selfhood: no longer would we be controlled by our reproductive systems.

In bed that night, after a brief internal dialogue as to whether I should say anything at all, I tell M. that I've had an abortion earlier that day and that he must have been the father. Color immediately drained from his face. I will never forget his look of horror. "Why didn't you ask me beforehand?" he asked, his voice trembling. I looked him in the eye and said: "This was my decision, not yours." He didn't protest, he just got up, silently, turned his back on me, put on his clothes and left. Since Reverend M. believed strongly in minority and women's rights, I didn't think he'd have a problem with my determining my future for myself, without consulting him. Clearly he did.

M. was actually a very sweet guy who I hope, by now, has forgiven my cavalier insensitivity to his religious faith. I didn't know at the time that such a thing as a pro-choice Catholic could exist. My disregard of M's feelings taught me that, if at all possible, women who choose to have an abortion should, if they can do it safely, consult with their partner, husband, boyfriend, lover, as well as their medical provider and support network.

I've been a widow for more than three years now. I've experienced the excruciating pain brought on by the death of a loved one. I can't excuse actions that result in the death of other human beings. I have also looked deep into my soul on those religious occasions where you are obliged to repent your sins: guilt, regret, shame and remorse about the abortion are just not there. Had I allowed those cells to grow, the course of my life would have been permanently altered in a way which was, at the time, completely untenable to me and absolutely unfair to it. Only occasionally, since Stew died, have I even wondered what those discarded cells might potentially have become.

I believed then and believe today that women have the right to make the decisions that affect our bodies and our lives. The decision whether or not to have an abortion is, in my view, ultimately up to the woman, her conscience and, if she so chooses, her spiritual or religious convictions. Five years after my abortion, Stew and I were blessed when I gave birth to Jessica, our wonderful, planned and much loved baby girl.

So now Dr. George Tiller is dead and his clinic permanently closed. In his lifetime, Dr. Tiller was one of a very few physicians who provided legal, medically indicated, late-term abortion care to women in distress. Last November, in a piece I wrote that touched on the meaning of the phrase 'domestic terrorism,' I reminded readers that, just over a decade ago, America witnessed a horrific killing spree, carried out by our own home-grown anti-choice terrorist movement, against pro-choice physicians like Dr. Barnett Slepian and now Dr. George Tiller. I received this e-mail in response:

Dear Judy,Reverend Spitz, you're the one who's disgraceful. You and your kind have no qualms about celebrating the deaths of physicians who provide abortion care, while you shed crocodile tears about an alleged holocaust of the "unborn." Forty-five million women in America have had abortions since they became legal; how many others suffered illegal abortions before Roe will never be known. We can't bring back the murdered physicians and clinic staff, but raising our collective voices in protest by telling our personal abortion stories is, in my opinion, a very appropriate way to honor their memories.

Regarding your comments about Barnett Slepian I need to inform you Barnett Slepian reaped what he sowed. Slepian was a babykilling abortionist and killed babies for money. James Kopp stopped him from murdering any more children and I'm glad he did. Your support for baby murderer Slepian is disgraceful.

- Rev. Donald Spitz, Army of God (12/25/08)

Judy Gumbo Albert was an original member of the 1960s countercultural protest group known as the Yippies -- along with Abbie and Anita Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Nancy Kurshan, the journalist Paul Krassner, the folk singer Phil Ochs and her late husband Stew Albert who died on Jan. 30, 2006. Judy co-authored The Sixties Papers: Documents of a Rebellious Decade (Greenwood Press, 1984) and The Conspiracy Trial (Bobbs-Merrill, 1970). Her articles can be found on line at CounterPunch, The Rag Blog, and on her website Yippie Girl.