The Battle of Chicago

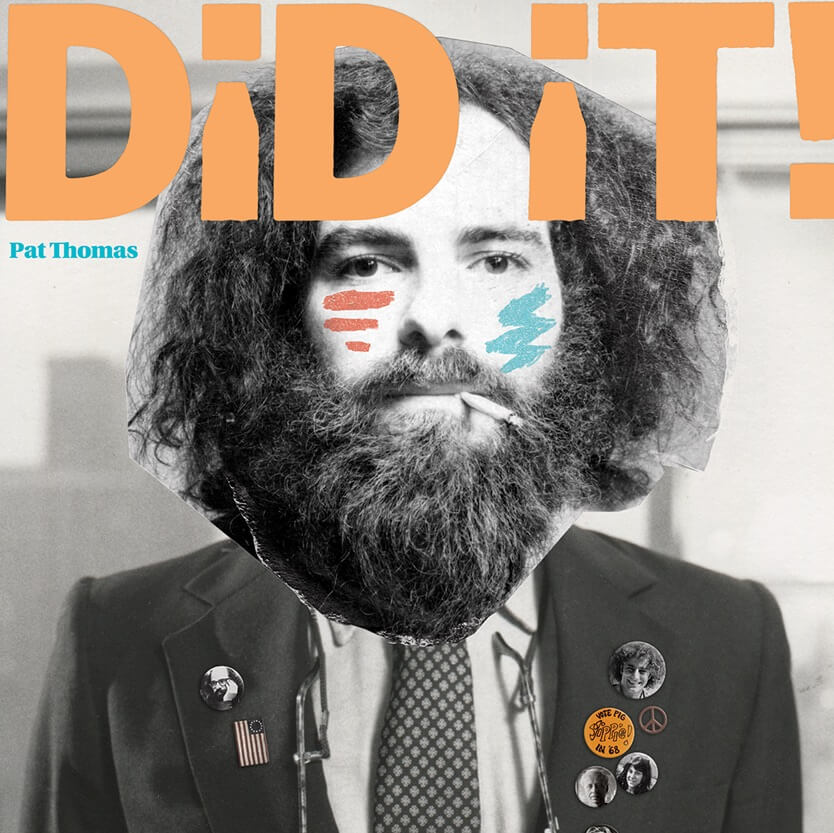

Forty years ago this week I was in Chicago at the Democratic Convention-- not as a delegate but as a member of the theatrical, countercultural, media-savvy protest group known as the Yippies. Then, as now, the Democratic Party was severely internally divided -- about race rather than gender, but especially over the war in Vietnam. We -- Yippie leaders Abbie and Anita Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and Nancy Kurshan, my then boyfriend and later husband Stew Albert, the folksinger Phil Ochs and journalist Paul Krassner -- came to the Convention to hold a Festival of Life and nominate a pig for president. Our candidate, Pigasus, would, we believed, be infinitely more attractive to young people than the Democrat's pro-war candidate Hubert Humphrey. Abbie, Anita, Jerry, Phil and Stew are all gone now, and, although I don't expect the events described here to occur in Denver, our country is, as in 1968, engaged in an immoral and illegal war overseas that has been used by our current elected officials to put more draconian restrictions on dissent and freedom of speech than I once faced confronting the Democrats in Chicago. What follows is my recollection of those events.

Who lead us to the war

It's always the young who fall

But look at all we've won

With a saber and a gun

Tell me is it worth it all? I ain't marchin' any more

No I ain't marchin' anymore

--Phil Ochs

WARNING...LOCAL COPS ARE ARMED

AND CONSIDERED DANGEROUS. (Yippie flyer)

Abbie always said we didn't come to Chicago to oppose the Democrats, we came to oppose the war. Well before the convention is due to begin, Abbie, Jerry, Stew and Paul have been negotiating with Chicago Mayor Daley's officials for permits. Permits to march and permits to sleep in the park. Permits for rallies and permits for the Festival of Life. Mayor Daley refuses to meet with them and sends a lower-level functionary, Deputy Mayor David Stahl, who both Abbie and Jerry ridicule because of his last name. But it's no joke. All Stahl does is stall.

Abbie, Paul, Jerry and Stew are not the only players in the Chicago permit drama. That honor also goes to Tom Hayden, founder of the decade's major student anti war organization Students for a Democratic Society, Rennie Davis, a well-known anti-war activist whose blood will be spilled a few days later, and Dave Dellinger, a much beloved and older (meaning in his 50's) pacifist and advocate for non-violent civil disobedience. They are the leaders of the larger, more traditional (traditional, that is, compared to the Yippies) anti-war organization called the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam or MOBE.

The MOBE is predicting thousands of young mainstream "Clean for Gene" supporters of anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy will descend on Chicago, while we Yippies use the underground press to try and attract countercultural youth with an imaginary scheme to put LSD in the drinking water. This act, FYI, is physically impossible; given the amount of LSD needed to make any difference. I know, I once put hundreds of packets red dye in the reflecting pool in Washington DC to protest the war and it just dissipated.

For the sake of historical accuracy, I will also disclose that we Yippies claim we're going to fuck on the beaches and burn Chicago to the ground. Ok, so, this sounds a little over the top threatening, but why would anyone in their right mind actually take Yippie seriously?

Mayor Daley is not a Yippie.

Nor is FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

By the time we roll into town, police forces from all over the state have been brought in, the cops are wired, the National Guard is mobilized, and tension is extremely high. Stew always believed that Mayor Daley, a Democrat, was set up by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to overreact to our Yippie exaggerations, so Americans would watch approvingly on television as hippies and anti-war demonstrators are rightfully put down and Richard Nixon gets elected as a law and order candidate.

Which is, in fact, what comes to pass. Mayor Daley denies all permits.

In fact, six months before the Convention, Mayor Daley had issued a "shoot to kill" order for demonstrators.

At most, 15,000 demonstrators show up for Convention week in Chicago. Perhaps it's closer to 5,000. We never really find out.

Thursday, August 22, 1968

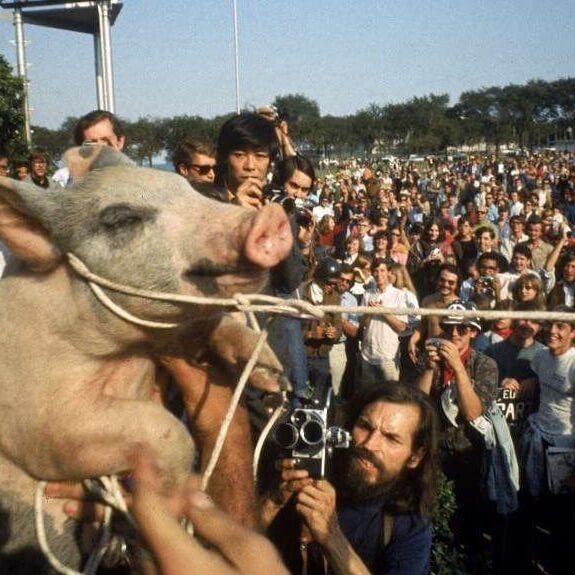

Our decision to run a pig for President leads to a giant internal Yippie fight.

Abbie, Anita and Paul want a tiny cute pig. Jerry gets incensed. It violates his sense of effective Yippie marketing: to adequately represent the candidates and all they stand for, the Yippie pig needs to be big, fat, ugly and mean. Jerry calls a meeting and, disregarding Stew's advice to let it be, reads a statement out loud to Abbie, Anita and Paul, denouncing Abbie as a media-hungry "ego tripper". Jerry even threatens to hand his statement out as a leaflet in Lincoln Park, if Abbie doesn't relent about the size of the Yippie pig.

This is what a serious ideological split in the Yippies comes down to -- the girth and poundage of our presidential candidate.

I'm embarrassed for Jerry. I don't understand the depths of his passion against Abbie but I know Abbie is fully capable of responding in kind. Never having experienced a dysfunctional family with two highly competitive male siblings, it seems to me that this is a really terrible precursor for the kind of society we Yippies are trying to create.

For the rest of the convention Abbie and Jerry aren't on speaking terms. But in some similarly familiar family way, this fight doesn't destroy their friendship. Abbie says:

We would not let a personal fight upset anything. Besides, we were both so dedicated that I, at least, realized that Jerry would cry at my funeral and make the right speech, and that I would do the same for him.

As, indeed, Jerry does cry after Abbie commits suicide in 1989.

Jerry recruits Stew, me, Nancy, Phil, and Yippie tai chi expert Wolf Lowenthal to go out to the nearby Illinois countryside and purchase the largest, smelliest, most repulsive hog we can find. His (or more likely her) name will be Pigasus.

After we pick out what looks to be a reasonably friendly 200 pound hog, the farmer makes us get into the pigpen and catch her ourselves. I'll never forget how hysterically funny that was --all of us falling, slipping and sliding, covered in mud and pig poop. Phil, being more fastidious, declines to participate but he's the one who pays the farmer. Somehow we manage to load Pigasus into our truck and take her back to Chicago for a press conference at the Civil Center the next day.

On our way back, with occasional oinking in the background, Jerry advocates, in his forceful, Jerry, ad-man way, that the Yippies demand Pigasus get treated as a legitimate candidate, with secret service protection and foreign policy briefings. Pigasus' platform, according to Jerry, will be that everyone in the world be allowed to vote in our election because America controls the world.

Today America may no longer be the world's only superpower, but I believe we Yippies were among the first to recognize the global reach of American elections. Perhaps Jerry's platform for Pigasus was right.

Friday, August 23, 1968. a.m.

Chicago Civil Center is jammed with local and national media. As soon as Jerry, Stew and Wolf take Pigasus out of the truck, she's arrested along with all her human companions, in front of television cameras, photographers and the press -- a genuine, perfect Yippie media moment. Later, as a jailed Stew and Jerry await arraignment, a fat burly Chicago cop comes up to them and says: " Boys, I have some bad news for you. The pig squealed."

We never see Pigasus again. Rumor has it she was sacrificed and eaten at a Chicago cop's barbeque.

Rest in Peace Pigasus: you served everyone well.

It's a rare thing you gave us -- allowing nice Jewish girls and boys to get so intimate with pork.

Sunday, August 25, 1968. a.m.

We demand a society built along the alternative community in Lincoln Park, a society based on humanitarian cooperation and equality, a society which allows and promotes the creativity present in all people and especially our youth.

(Yippie flyer written by Abbie for Lincoln Park detailing 18 Yippie points for our ideological platform and program)

Today is the day scheduled for our Yippie Festival of Life, as a counter to what we call the Democratic "Convention of Death."

Among the missing in Lincoln Park are the bands -- scared off, because all the major media, mainstream and alternative, are predicting riots. Abbie is especially angry. He feels betrayed; he thought many of the famous musicians he invited were his friends.

The only band to show up is the MC-5, a macho, overtly political, hard rock band out of Ann Arbor, managed by Yippie John Sinclair. Abbie, who is an excellent promoter but not especially a promoter of rock concerts, neglects to provide electricity, so wEd Sanders, a well known poet and lead singer of the Fugs, helps the MC5 plug an orange 300 foot extension cord into a nearby hot dog stand. MC5 founder Wayne Kramer remembers:

At one point there were Chicago police helicopters hovering over us. We were doing this very experimental piece that's out of time and out of key -- space music -- and I'm playing this feedback, and the helicopter is coming in -- whomp, whomp, whomp. And it was all just perfect. But the minute we stopped playing the altercations started to break out. The police kind of ratcheted up their assault on people.

Immediately after they finish, the MC5 leave the Park as quickly as possible. I'm standing with Stew and Abbie close by the truck where the band had played, when Abbie hears over his walkie-talkie that the cops are entering the park some distance away. I look over at Stew and -- o my god -- blood is running down through his blond curls and over his forehead.

No uniformed cops are to be seen anywhere in the vicinity.

I'm not usually afraid of blood. Doesn't matter. I panic.

So does Abbie.

Stew's a little woozy and sits down on the grass.

"You're bleeding," I tell Stew. As if he didn't know that.

Isn't it amazing the stupid things you say in a crisis?

Abbie has the presence of mind to persuade the medics to take Stew to the hospital; his wound requires six stitches to close. The doctors tell Stew the wound was likely made by a blackjack. We figured it had to be an undercover cop.

Stew's is the first blood to be shed in Lincoln Park that Convention week.

Sunday, August 25, 1968, p.m.

All day long, Park employees are putting up signs saying there will be an 11 p.m. curfew. Stew, his head bandaged but in great spirits, and I and the rest of the Yippies are determined to ignore it.

By 11 it's pitch dark. Except that behind us, over the rolling hills of the park and through a few tall trees, you can make out something approaching. Then, over a hill, silhouetted against the darkness and trees, backlit by huge tall glowing lights, swirling at least 8 feet off the ground, comes a dense white/grey fog in front of which a line of ghostly cops has materialized, marching in formation.

I'm in the middle of a live action war documentary.

Stew and I, Jerry and Nancy stand up quickly. By now we smell something strange, toxic and burning -- tear gas.

The line advances.

It's the scariest thing imaginable.

Except I don't feel scared.

I'm exhilarated..

We'd learned earlier in the day to carry bandannas and scarves to put over our mouths to be able to breathe, but the grey, floating gas burns inside our noses, sticks to the bandannas and to our clothing. The bandannas are useless.

Jerry and Nancy disappear. No yelling or screaming, the silence is eerie. The line of cops moves in closer behind us, the fog gets thicker, like a San Francisco fog gone bad. I observe other protestors, their silhouettes illuminated against the gas, running in the distance.

It's difficult to breathe. I choke up; tears run down my face. Everything is in slow-motion.

But I'm not afraid. Stew is looking out for me, we're running, together, side by side, propelled by an urgent imperative to get away. The tear gas unites us in a brand new kind of intimacy and commitment.

I feel protected.

I feel courageous.

I am powerful.

I'm fighting for what I believe.

This is fun!

Over a ridge and down in a small valley ahead of me, I see Allen Ginsberg, author of the epic poem Howl, in which he saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness. Allen is sitting on the grass, lotus position, balding, long curly dark hair, in a circle with about a dozen friends and acolytes. Ommmmmm.....they chant the mantra together as if to remind the universe that even in the midst of chaos all life is interconnected, and its soothing sound echoes through the tear gas ....Ommmmmmm....

Allen is a Yippie and we run toward him.

"Boy, he's not going to last very long", I think to myself.

The gas is getting very, very strong and potent.

A few seconds after we run past, Allen's group is forced to scatter.

So much for mantras, gentle poets, and non-violent, loving spiritual practice.

Were the Chicago cops fulfilling their personal piggy karma?

Monday, August 26, 1968

And the wise men walked in their Robespierre robes

Through Lincoln park the dark was turning

The towers trapped and trembling, and the boats were tossed about

When the fog rolled in and the gas rolled out

In Lincoln Park the dark was burning

-- "William Butler Yeats visits Lincoln Park"by Phil Ochs

Someone says that this particular type of teargas has been outlawed for use in Vietnam.

That may be just a Yippie urban legend.

Someone else says the lights were mounted on garbage trucks. Which turns out to be true.

Nancy, Anita and I bring small cans of tempera paint to make protest signs. We can't think of anything else to do. Wolf Lowenthal and Abbie lead groups of demonstrators in practicing tai-chi, we shout WA-SHOI together in the vain hope we'll be able to get away as a crowd. Jerry and Stew try to come up with a strategy for dealing with the coming curfew, nothing seems appropriate.

We don't feel afraid, or depressed. At least I don't. Or maybe all of us are in denial and none of us are showing it. Instead we're almost manically exhilarated, we tell war stories of how we got away, of how striking black bus drivers gave us the Black power fist sign, of seeing a few policemen beat an ignominious retreat.

The battle of Chicago has begun.

Some time after dark a police bullhorn orders us to leave Lincoln Park or violate curfew. The Yippie gang, Stew and I and about 1000 other protesters jeer, hoot, holler, jump up and down and chant an old anti-draft slogan, which feels perfectly appropriate,: "Hell No, We Won't Go."No curfew for us -- the park belongs to the people.

Then, for some reason, a cop car drives into Lincoln Park. It's a total provocation. So hundreds of us immediately surround it. Naturally, and also immediately, the police use this as an excuse to invade the park to rescue their comrades and attack us.

But not just demonstrators, now the police are singling out reporters wearing business suits; reporters with credentials who they will club and beat bloody.

I throw my 2" bottle of tempera paint at the offending police car.

Doing that is pretty scary.

My bottle bounces off the roof.

Which makes me really happy. Usually I throw like the girl I am. At least this time I actually manage to hit something. This tiny act of confronting authority somehow overcomes any fear I have left and, for the first time in my life, I feel truly free.

I'm actually euphoric.

Forty years later, this is what I've come to understand about my time in Lincoln Park: In every woman's life, opportunities will arise to face your fears. I'm not suggesting throwing a can of paint at a police car -- only that it is very important to recognize when you're actually in that unique "face my fear" moment. In such circumstances, take action. Don't delay. Don't procrastinate. Don't over think the consequences. By facing your fear, you will discover inside yourself the courage to put your life-- and your freedom -- into your own hands.

I never turn back.

Early Wednesday August 28, 1968

It's 1 a.m. The park side of Michigan Avenue, across from the Hilton Hotel on where the delegates are staying, is lined with young National Guardsmen pointing their bayoneted rifles toward the sky. As soon as Stew and I see the Guard coming, we and a few thousand others start yelling and screaming: Join us, Join us.

For the record, Stew and I never yelled "baby killer" at anyone. Neither did anyone we knew. Nor, in all my years as an anti-war activist, did I ever hear anyone yell that. Plus I never got reports of anyone yelling that or overheard anyone say they saw it happen.

I've come to believe that the image of protestors yelling "baby-killer" at GIs is a stereotype perpetrated by red-meat conservatives to swift boat the anti-war movement.

However, I'm also confident that one or two of us did yell "baby killer'.

After all, there will always be a person to fit the stereotype.

To any military person who, actually and in reality, was wrongly yelled at forty years ago by an anti-war activist, I want to apologize on behalf of the 1960s anti-war movement.

Unless of course you're Lt. William Calley.

Who actually massacred babies in the village of Mi Lai.

Like I said, you can always find a person to fit the stereotype.

Above the lines of Guardsmen, facing the demonstrators, room lights are blazing on the many floors of the Hilton Hotel, while delegates in fancy coats and women in long dresses and fur stoles enter and exit the front lobby. I bet those delegates never imagined that when they paid extra money to reserve a room with a Park view, it came, free of charge, with demonstrators, National Guard, spotlights and tear gas.

Together Phil Ochs and I walk the lines of national guardsmen. Phil is wearing his usual slacks and suit jacket with an American Flag pin. On the inside where it can't be seen unless he shows it to you, Phil also wears a peace button. Jerry teases Phil about this incessantly, insistent, in his intense Jerry Rubin way, that Phil show his true colors by wearing his peace sign on the outside, and flag pin on the inside.

Phil never complies.

Phil was born in El Paso Texas and really loves America. Even when he's being gassed along with the rest of us. As we walk, Phil introduces himself to the impressed guardsmen and asks if they've ever heard his songs. Like "I Ain't Marching Anymore."

Many nod.

"I once spent $10 to go to one of your concerts" one complains. "I'll never do that again."

In 1968, $10 was a lot of money. Phil stops and talks directly to the guy, explaining why he is opposed to the war. The Guardsman starts to smile, and even lowers his rifle a little bit, very appreciative that a celebrity like Phil is speaking to him like a real person.

Phil believes in democracy.

Phil shows me what it means to be an American patriot.

The riots, gassing and beating of demonstrators protesting a disastrous war at the Democratic Convention in Chicago 1968 became a turning point in the history of American dissent. Many Americans, who already disapproved of the Vietnam War, were shocked and horrified at what they witnessed taking place on the streets of Chicago. Walter Cronkite, the most famous news anchor of the day observed: "They're beating our children."

And we in turn chanted: "The whole world is watching."

When Stew and I grow tired of the fighting, we make our way around the police lines, followed at some not too discreet distance by a relentless crew of plain-clothed cops. Back home, we jump into bed and make love that feels especially delicate, sweet and tender because, who knows, it could be our last time. Tomorrow we may be in jail or perhaps even dead.

At 11 p.m. we turn on the television to watch ourselves on the local news.

We are Yippies after all.